Island

July 2020: Michael's email michaelgalbreth@gmail.com has been hacked. Any messages received from that email are illegitimate.

Etheridge

He had been our Destroyer, the doer of things

We dreamed of doing but could not bring ourselves to do.

– Etheridge Knight

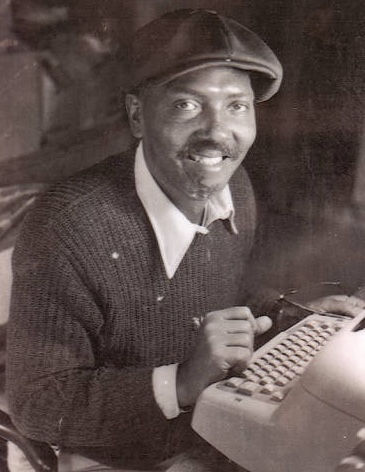

Knight at typewriter, ca. 1960s, courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

A recent article in the New York Times caught my eye. It was about Etheridge Knight. The article was a review of a recently published book called "To Float in the Space Between: A Life and Work in Conversation With the Life and Work of Etheridge Knight" by the poet Terrance Hayes. It's Hayes' first book of prose and is described by the reviewer as a "speculative biography" and as "motley and adrift as Knight himself." The review reveals, albeit in a sideways way, that Hayes never knew Etheridge. But I did. For a short while, Etheridge was my friend.

I moved to Memphis in the fall of 1978 to attend Memphis State, to re-enroll in school and finally acquire the degree I started a few years before. As an undergraduate, I still had some required courses to fulfill, one of which was English. I selected a class on poetry. It was taught by a young African American from the north somewhere, and whose name, most unfortunately, I've long forgotten. It was a wonderful class, one of my favorites. There were rarely any assignments, i.e. homework, and most of the classes were comprised of aloud readings and critiques of various works. It was here that I enjoyed a full dissection of "Howl" and learned that Robert Frost was not such a "square." It was also the class that I first heard about and read the poetry of Etheridge Knight.

One of the textbooks used for the class was the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry. Buried within this volume among the illustrious, all-time faves such as Cummings, Frost, and Dickinson was this new voice (for me) of Etheridge Knight. I suspect he was chosen to introduce the young white faces in this class to an important African American poet, and to shock us out of our over-intellectualized properness. Whatever the reasons, it worked for me.

This was my introduction to Etheridge:

Hard Rock Returns To Prison From The Hospital For The Criminal Insane

by Etheridge Knight

Hard Rock/ was/ "known not to take no shit

From nobody," and he had the scars to prove it:

Split purple lips, lumbed ears, welts above

His yellow eyes, and one long scar that cut

Across his temple and plowed through a thick

Canopy of kinky hair.

The WORD/ was/ that Hard Rock wasn't a mean nigger

Anymore, that the doctors had bored a hole in his head,

Cut out part of his brain, and shot electricity

Through the rest. When they brought Hard Rock back,

Handcuffed and chained, he was turned loose,

Like a freshly gelded stallion, to try his new status.

and we all waited and watched, like a herd of sheep,

To see if the WORD was true.

As we waited we wrapped ourselves in the cloak

Of his exploits: "Man, the last time, it took eight

Screws to put him in the Hole." "Yeah, remember when he

Smacked the captain with his dinner tray?" "he set

The record for time in the Hole-67 straight days!"

"Ol Hard Rock! man, that's one crazy nigger."

And then the jewel of a myth that Hard Rock had once bit

A screw on the thumb and poisoned him with syphilitic spit.

The testing came to see if Hard Rock was really tame.

A hillbilly called him a black son of a bitch

And didn't lose his teeth, a screw who knew Hard Rock

From before shook him down and barked in his face

And Hard Rock did nothing. Just grinned and look silly.

His empty eyes like knot holes in a fence.

And even after we discovered that it took Hard Rock

Exactly 3 minutes to tell you his name,

we told ourselves that he had just wised up,

Was being cool; but we could not fool ourselves for long.

And we turned away, our eyes on the ground. Crushed.

He had been our Destroyer, the doer of things

We dreamed of doing but could not bring ourselves to do.

The fears of years like a biting whip,

Had cut deep bloody grooves

Across our backs.

source: The Poetry Foundation

"Holy shit," I thought to myself.

I was already a student of, and enamored with, the southern vernacular of Faulkner and Agee, but this was something different. Different because these were words specifically meant to be read aloud, to be spoken, shared and heard. I loved it.

Each study of individual poets was accompanied by some background biographical information. Etheridge was more tangible to me than the other poets we studied. His street language was one reason. We learned that Etheridge was a convicted criminal and had done time where and when he began writing. His words were true. He lived them. Furthermore, Etheridge was among the living. He was still around. Not only that, we were told that he lived in Memphis.

"Holy shit," I thought to myself, again. He's right here. So I set out to meet him.

Etheridge Knight was in the Memphis phone book, his number and address listed in the white pages. Rather than calling, I summoned my courage and drove to his place. Etheridge lived on the upper floor of a small, nondescript two-story brick apartment complex just east of downtown. I knocked on his door and he answered. I explained myself. Etheridge was then, as I always subsequently knew him to be: wobbly, and slightly slurring, but gracious and gentle. Still, he must have wondered, at first glance, what this naive white kid, twenty years his junior, was doing standing at his door. When he understood my enthusiasm for his work, he seemed touched. We became friends.

Etheridge showed up for class one day, by my invitation, to read some of his works. The instructor was pleased, if not impressed. As usual, Etheridge was barely coherent, that is, until he began reading. When Etheridge read his poetry he did so from memory, clear and crisp. In retrospect I felt negligent for not having the sensitivity to offer Etheridge compensation, but that didn't stop Etheridge from asking anyway. I gave him what I had, which wasn't much.

I later invited Etheridge to participate in a large group exhibition that I helped to organize called Up Front. I remember that he brought a bottle of Jack Daniels to our initial organizational meeting. He passed it around to share, which most of us did, straight out of the bottle, and not bothering to wipe the mouth, making the ritual truly communal. I'll never forget this simplest of gestures that, even for a moment, signified our unity as an art tribe. We were in it together.

"Up Front" exhibition poster, 1980, front and verso

Etheridge was an exceedingly wise and kind, yet damaged person. He was an alcoholic and drug addict, and was always fucked up when I knew him. I eventually had to distance myself from him in order to get away from his constant begging for money. His biographies note that he was married while he lived in Memphis, and had a child as well, but I didn't know this. I never saw his family. Nor did I ever hear Etheridge refer to them. After the "Up Front" show, he disappeared and I soon left for Houston. I lost touch with him. Etheridge was great. He was the first real writer that I knew.

Etheridge Knight, poetry reading, undated

_________________________________

December 31, 2018